Suited up and carrying my board, I walk toward the gate where a bundled-up attendant aims his electronic zapper at my lift ticket. We exchange “how you doings,” And I continue walking out to the edge of the slope while skiers already mounted into their bindings zip on past me.

Suited up and carrying my board, I walk toward the gate where a bundled-up attendant aims his electronic zapper at my lift ticket. We exchange “how you doings,” And I continue walking out to the edge of the slope while skiers already mounted into their bindings zip on past me.

There’s a bench at the cusp of the downgrade, but several snowboarders have claimed it to buckle in. My new rig includes the latest in step-in bindings, so dropping the board with a resounding “thwack” onto the crisp and freshly groomed surface of the snow, I step my front foot into the maw of the binding, raise the back riser and engage the locking clamp. A safety strap to keep the board from getting away unattached is snapped to the top of my boot. One foot in, one to go. The back foot is a repeat of the first, minus the runaway strap. If the board is not on nearly perfectly level ground, it will begin to move downhill the instant the rear boot is clamped into the binding. But I am ready to go, and with a slight jump, I position the board into the grade and begin to slide into the slope, slowly at first. I find it difficult to believe that I am seventy-one years old.

The laws of gravity, friction, adhesion and a host of other dynamics I barely understand all come into play, and I am quickly accelerating down a wide swath of sunlit snow. Around me others on snowboards and skis are doing the same. This is a “Green Circle” run, a Novice or Beginner’s access run that leads to a cornucopia of ski trail options. Near the bottom of the run, a turn to the left will open to an extended easy run of gentle switchback turns all the way to the bottom of the mountain. A turn to the right, however offers a choice of several Black Diamond or advanced runs. It’s my first run of the day and my inherent conservatism usually dictates an easy start. But what the hell, I am already carving effortless arcs on the green, so let’s go for it, right from the start.

Cutting away from the pack of snowplowing skiers and nervous looking beginning boarders, I let my board run flat and zoom toward the sign marked with a large black diamond and the words “Midway, Advanced Skiers Only.” The surface of snow ahead of me seems to come to an abrupt end. As I approach the edge, I check my speed, sliding laterally across the slope to the point of the drop-off that begins the Black Diamond or “expert” run. Pivoting on the edge of the slope, I turn the nose of the board directly into the line of least gravitational resistance, the “fall line.”

I am looking down a white wall, and the sense of acceleration is immediate. A rush of adrenaline hits me as I turn my right shoulder to my left, my hips automatically follow my shoulder, and with my knees flexed and my toes pushing on the edge of the board, the entire organic mechanism that is me and the snowboard begins to turn across the face of the hill. It all takes place in a fraction of a second, and as the sharp, steel edge of the board cuts and digs into the surface of the snow, my acceleration is arrested. But because of the severity of the grade, the slowdown is not much noticed. I am fucking flying.

Immediately leaning forward, I throw my shoulder back into the direction from whence I came. This time I’m turning back across the slope, but now it’s my heel edge that biting the surface, and in a counter-weight to my forward velocity, I’ve dropped into a crouch with my butt hanging back into the grade of the hill and out over the snow. This is all taking place in real time, at high speed and with no time to actually think about what has to be done. My interior landscape is a precarious balance of intense concentration and near complete relaxation. The air is rushing past my ears and the sound of the edges of the board fighting for a grip on the surface rises like the screaming of fast freight on a curving track. One bad move, a single lapse of focus, one misjudgment in a nearly infinite mix of factors and there are consequences that can approach the life threatening. You do not want to make any mistakes.

The degree of the descent eases and the run opens out into a wide bowl, allowing me to aim myself up and around the rim of this saucer-like indentation in the side of the hill. The turn up into the bowl immediately has a dampening effect upon my speed, and at very top edge of the cup, I execute a sharp cutting turn back into the fall line, down and out of the bowl and into the next drop in terrain.

It’s at this point that the trail merges into a wider and steeper run from the top of the mountain. It’s a little like a mixing bowl of lanes on the Jersey Turnpike near the George Washington Bridge. On a weekend, there can be throngs of skiers and boarders all flying downhill and all seeking ways to share the space. There are no lane markers, but theoretically, the uphill person is responsible for the safety of those below. That theory always seems to get wobbly in the heads of too many of the hormone-charged adolescent males whose only mode of riding is flat out down the fall line. I am very careful on merging trails, more so on those rated “Advanced.”

The rest of the run is just variation on all of the above, and too quickly it seems, I find myself at the bottom queuing up in line for the chair lift or gondola that will take me back up to the top where I can choose another of the always interesting and exciting ways to work my way back again to the bottom. Standing in line reflecting upon the preceding moments of riding, I realize that riding a snowboard is akin to entering a closed system, one that combines in varying measures, pure bliss, borderline terror and an ever-present possibility of experiencing a sense of kinetic grace otherwise granted only to the Barishnikovs and Nureyevs of this world.

And now it’s over once again for another nine months.

In the Philadelphia Flyers loss last Thursday night to the Florida Panthers, I watched the Panther’s Corey Stillman score a goal that spoke to a level of eye-hand coordination that approaches the miraculous. Stillman was a major contributor to the Carolina Hurricanes team that won a Stanley Cup in 2006.

In the Philadelphia Flyers loss last Thursday night to the Florida Panthers, I watched the Panther’s Corey Stillman score a goal that spoke to a level of eye-hand coordination that approaches the miraculous. Stillman was a major contributor to the Carolina Hurricanes team that won a Stanley Cup in 2006. Suited up and carrying my board, I walk toward the gate where a bundled-up attendant aims his electronic zapper at my lift ticket. We exchange “how you doings,” And I continue walking out to the edge of the slope while skiers already mounted into their bindings zip on past me.

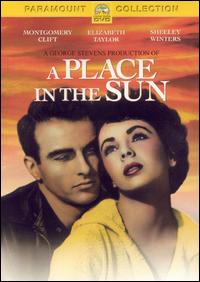

Suited up and carrying my board, I walk toward the gate where a bundled-up attendant aims his electronic zapper at my lift ticket. We exchange “how you doings,” And I continue walking out to the edge of the slope while skiers already mounted into their bindings zip on past me. Watching the Turner Classic Movies’ presentation of 1951’s blockbuster hit “A Place in the Sun,” with three other pre-war WW II-vintage friends, my own deconstructions of how the film had not aged all that well over the intervening fifty-eight years, raised some hackles with one of my fellow viewers. She had loved the movie in 1951, and did not appreciate hearing the ironic delight as we pointed out the now campy, corny and embarrassing aspects of the production.

Watching the Turner Classic Movies’ presentation of 1951’s blockbuster hit “A Place in the Sun,” with three other pre-war WW II-vintage friends, my own deconstructions of how the film had not aged all that well over the intervening fifty-eight years, raised some hackles with one of my fellow viewers. She had loved the movie in 1951, and did not appreciate hearing the ironic delight as we pointed out the now campy, corny and embarrassing aspects of the production. The Surrealist movement of the early to mid-twentieth-century has not held up very well. It’s all come to seem and feel rather quaint; the soft clocks, the agoraphobic landscapes and supposedly jarring juxtapositions. The avant-garde aspects of life as it’s now experienced has rendered the entire idea of “surrealism” irrelevant.

The Surrealist movement of the early to mid-twentieth-century has not held up very well. It’s all come to seem and feel rather quaint; the soft clocks, the agoraphobic landscapes and supposedly jarring juxtapositions. The avant-garde aspects of life as it’s now experienced has rendered the entire idea of “surrealism” irrelevant. The movie wasn’t really doing so hot

The movie wasn’t really doing so hot Prine’s sly take on American popular culture in the nineteen-forties, maybe early fifties, nails the boundaries of Hollywood exotica in those times. But at least “Sabu the Elephant Boy” was relatively close to the real thing.

Prine’s sly take on American popular culture in the nineteen-forties, maybe early fifties, nails the boundaries of Hollywood exotica in those times. But at least “Sabu the Elephant Boy” was relatively close to the real thing.  In the Arts and Leisure Section of today’s New York Times, a case is made for the influence of Edward Hopper upon the course of American photography. Seems like a no-brainer.

In the Arts and Leisure Section of today’s New York Times, a case is made for the influence of Edward Hopper upon the course of American photography. Seems like a no-brainer.